Activity 3: The Chinese in 19th century Australia

Key inquiry questions

- What do we know about the lives of people in Australia's colonial past and how do we know?

- What were the significant events and who were the significant people that shaped Australian colonies?

The core literary texts used in this topic are New gold mountain and Seams of gold, both written by Christopher Cheng. The focus explored in this sequence is Australia's colonial past: the Chinese in Australia in the 19th century. Assist students to use and analyse primary and secondary sources to answer the key inquiry questions: What do we know about the lives of people in Australia's colonial past and how do we know? What were the significant events and who were the significant people that shaped Australian colonies? Guide students in making connections between local and global events by using a parallel timeline.

Task 1: The arrival of the Chinese in Australia

In the 19th century Australia experienced a huge increase in population. Most of this was the result of immigration. Workers were needed to support the growing colonies and, since the birth rate was low and the transportation of convicts had ceased, people were enticed to come to the colonies. In 1851 gold was discovered in Australia and goldminers came from across the world in their thousands to share in the wealth. Use the questions generated by the students in the previous topic to guide inquiry in this topic.

Students compare and analyse secondary source materials to address the following questions:

- When did different groups of Chinese people come to Australia?

- Why did they come?

- What did they do in Australia?

- From what parts of China did they come? Who were they?

- Is information consistent across texts?

- Why might differences between sources occur?

- Are there differences in fact or opinion?

- What are some solutions to the problem of having texts that don't agree? Discuss.

- How reliable is each source? What makes you think so?

Students complete the following chart:

Parallel timeline

Historical events do not occur in isolation. They are influenced by local and global contexts. Students will make connections between the events on the timelines.

Introduce the concept of chronology.

Model researching timelines of China's history in the 19th century. Search for the Taiping Rebellion (civil war), the Opium Wars and the Boxer Rebellion. See also texts about the British in China.

Read pages 9–12 of the factual text China the story of a nation … and its relationship with Australia (Onslow 2012) or a similar text.

Students research timelines for events in Australia's history, for example: Federation; the 1890–1894 drought; widespread strikes; and the discovery of gold. Return to the Harvest of Endurance scroll.

Ask students to plot the key events in China and Australia on a parallel timeline. Students may use pictures and words when recording events. See pages 16–19 in Connecting with History: strategies for an inquiry classroom (Ditchburn & Hattensen 2012).

Use sources from each state and territory (see the References section above).

| China

1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920

|

| Australia

1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920

|

| Local or State/Colony

1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920

|

Display the timeline and add to it throughout the unit of work, making new connections as more events are added.

With the students list the push and pull factors that influenced Chinese immigration to Australia in the 19th century. Push factors are things that are less favourable about where a person lives, and pull factors are things that appear favourable somewhere else, and thus attract people.

| Push factors

| Pull factors

|

|

|

Ask students to address the following question:

What push and pull factors influenced the characters in New gold mountain?

Task 2: Chinese culture, beliefs and traditions

Ask students to locate source material about the language and culture of the Chinese in Australia in the 19th century. While most Chinese who came to Australia were from Guangdong Province and spoke Cantonese, that was not always the case.

Invite a guest speaker from the local Chinese community to talk about their traditions and beliefs or send interview questions by email.

Visit a local temple, joss house or museum.

While reading New gold mountain students record information about the language, culture, customs and beliefs of the characters in the novel. 'Respect' is often referred to in the text. Locate examples of this in the novel and categorise them. For example, some mentions may be about respect for tradition, others may be about respect for family or ancestors.

Compare the information in the novel with that located in source materials. Students work in groups to create a collage of symbols or images that they associate with China. This may require a little prompting such as a Google search of 'Images' when searching 'China'. Common images appear for the Great Wall of China, dragons, pagodas, bridges and lanterns.

Display the collages and discuss differences between group projects. Differences in students' backgrounds and cultural knowledge will determine what is represented.

Task 3: Sketch-to-stretch

Model the visualising strategy, sketch-to-stretch, by thinking aloud while reading from New gold mountain. For example:

Wednesday, September 5 (day four)

'As I read this I'm making a movie in my head. I can picture one of those really rainy days when it's grey and miserable and the rain doesn't let up. Then I see Shu Cheong in his blue pants and tunic that look like pyjamas and he's imagining that he's back in China. I think I can see a thought bubble and inside it there's a picture of a rainy day with Shu Cheong in it and he's laughing. Next I can see a tent. It's not like the brightly coloured synthetic ones we see today but just dirty off-white canvas with ropes holding it to the muddy ground. I can see Shu Cheong with his clothes plastered to his body in the wet. Next I see him falling forward and landing on his knees. I can see the water dripping off his clothes and his hair and he's covered in mud. The look on his face is sad. He looks as though he could cry. Then I see him trying to wash the mud off his clothes while he's still wearing them. I can see the dirty marks getting bigger and bigger as he scrubs.'

Sketch the pictures as you think aloud. Stick figures will do.

Students choose a descriptive passage in a diary entry from Monday, September 24; Tuesday, October 2; or Thursday, January 17 then meet with others who have selected the same entry. They read the passage silently and list any unfamiliar words or phrases, then share their lists and help each other to work out the meanings. Any words that cannot be worked out in this way may be looked up in a dictionary.

When students agree that they understand the passage ask them to locate parts of the text that might be hard to illustrate. Students share their ideas.

Model as many examples as are necessary for students to work independently. An example is in the entry dated Tuesday, October 2 when Shu Cheong is lying along the branch and is glad no one saw him swimming in air. He could be drawn with his head turned as though he were looking for someone and with a worried look on his face; a wrinkled brow.

Read the first paragraph of Shu Cheong's diary entry for Thursday, November 22 and use the sketch-to-stretch visualising strategy to represent what is read. Encourage students to use their knowledge of the goldfields to fill in details in the sketch.

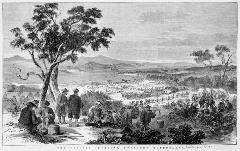

The Chinese Invasion, Northern Queensland, Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria

The Chinese Invasion, Northern Queensland, Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria

Students share their work with the class and comment on each others' sketches and how they have interpreted the passage in different ways. Students justify their comments by using examples from the text.

View the sketch below and have students compare it with their own sketches. Ask students if they think Christopher Cheng may have used this sketch to inspire his description of the Chinese walking into Lambing Flat.

This sketch from the Illustrated Australian News, 2 July 1877, reflects contemporary fears the Australian colonies would be 'over-run' by Asian immigration (Illustrated Australian News, National Library of Australia).

Task 4: Artefacts as primary sources

When analysing artefacts, use the Useful questions for 'interrogating' an object on page 2 of Exploring a 'time capsule' of evidence from the National Museum of Australia.

In the preface to New gold mountain Shu Cheong says, 'All I have is Baba's small bag with his ring and weighing scales, his China dirt, cap and coins, which the men gave me'.

Ask students to imagine that this small bag, with all its contents intact, was discovered in an old trunk in 2013. The trunk which is known to have belonged to Shu Cheong now belongs to one of his descendants. Shu Cheong's diary has not yet been found.

What are some of the inferences that could be made about Shu Cheong and his life using only the trunk, the bag and its contents and Shu Cheong's name as sources?

What other sources could the descendant use to support the inferences?

Ask if students have anything in their families that have been passed down through generations either with a story attached or as a mystery.

For example, I have a locket that was given to me after my father died. It contained a lock of hair which I foolishly threw away because my father had said it would bring bad luck. No one in the family knows very much about it. I've seen photographs of my grandfather, who was born in 1891, wearing the locket when he was a young man. An Australian sixpence is attached to one side of the locket but very slightly overlaps the edges, so my sisters and I think it covers a name and was added some time after the locket was originally made. The coin does not show the date but we know it must be dated 1910 because the monarch on it is Edward VII who died in 1910 and the first Australian silver coins were minted that year.

Task 5: Seams of gold

Students read the short novel Seams of gold by Christopher Cheng. Seams of gold was inspired by a small sewing box in the National Museum of Australia's collection.

Students write a short summary of the novel.

Go to the website of the National Museum of Australia: Making tracks which includes a synopsis of Seams of gold.

Students read this synopsis and, working in pairs, compare it with their partners' summaries. Students provide feedback to their partners on accuracy of information, inclusion of key facts and appropriate sequencing of events.

In small groups students read and discuss the questions on the website. These are all evaluative questions. Discuss the way context may influence responses. For example a Chinese 12-year-old in Australia in the 1850s might think very differently to a 12-year-old in Australia today.

As a class discuss the historical concept of perspective or point of view.

- How does context influence our attitudes and opinions?

- Can we change our opinions?

- Can we change the opinions of others?

- Can we empathise with others who do not share our perspective?

Task 6: Making inferences from artefacts

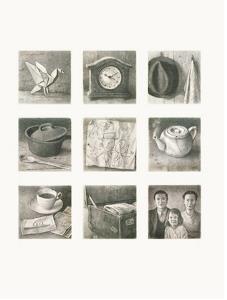

Illustration from The Arrival by Shaun Tan. Courtesy of Hachette Australia

Illustration from The Arrival by Shaun Tan. Courtesy of Hachette Australia

Artefacts are found in museums, libraries and galleries. Can these artefacts stand alone as evidence?

In The arrival the following page displays items in the family home.

If we had only this page of the book what could we infer by examining the artefacts?

Students complete the following chart.

| Question

| Inference

| Why do I think that?

|

| How wealthy is the family that owned these items?

|

|

|

| Did the family in the picture own the items?

|

|

|

| Did all of the items come from the same house?

|

|

|

| Are the items from the same era?

|

|

|

| Where were these items found?

|

|

|

| What happened to the family that owned the items?

|

|

|

| Were the owners greedy?

|

|

|

Can we be certain that our inferences are correct? What other sources could help us build a body of evidence about the artefacts?

Task 7: Interrogating an object

Each student chooses an item from a selection brought to school by fellow students, from a local history museum or one found in an image search.

Ask students to use the Useful questions for 'interrogating' an object to analyse the item.

Using Seams of gold as a model, students write a brief narrative that explains this item in a believable historical context.

Task 8: The riot at Lambing Flat

The roll-up banner used in the Lambing Flat riots, public domain

The roll-up banner used in the Lambing Flat riots, public domain

Young, a town in NSW, was once known as Lambing Flat. Thousands of Chinese shared the goldfields there with European miners. Anti-Chinese sentiments were running high and resulted in riots against the Chinese in 1860 and 1861. Similar riots occurred across the country. Students may research local sites and compare causes and effects.

Local students could visit the Lambing Flat Museum in Young. The Roll Up Banner used in the riots is on display there.

When analysing documents and images, remind students to use the Useful questions for 'interrogating' a document.

Read Shu Cheong's account of the Lambing Flat riot in his entry dated Tuesday, July 2. This event was reported in newspapers across the country. Demonstrate to students how to search the Trove database for newspaper items about the riot. What search terms can you use, and how does this affect the search results? How many articles can you find? In what ways can you narrow your search? Try narrowing by decade, year, month, or by newspaper or category.

The Bendigo Advertiser, Wednesday 3 July 1861, has a short report of the incident with little detail. Can you locate this item? (Answer found here.)

The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, Thursday 11 July 1861, printed an article based on an account by Mr Henley (see diary entry Saturday, March 16) and a letter to the editor on Saturday, 20 July 1861.

Ask students to read the newspaper items and summarise the point of view of the authors. They should refer to emotive and evaluative language contained in the texts when explaining their summaries.

Compare the reports.

Some of the rioters were placed under arrest and a large mob rioted once more to secure the release of the prisoners. Have students read the report of this in Bell's Life in Sydney, 20 July 1861. The text is not easy to read and would best be done as a whole class activity. What is the point of view of this author? List words that show bias from the text. Compare the points of view of this and the previous authors.

Students identify and analyse source materials that illustrate the attitudes of the miners towards the Chinese.

With the students, read about Anti-Chinese sentiment in the 1850s in the My place for teachers website.

What were the causes of the anti-Chinese riots? Discuss the events and the descriptions of the Chinese. It is clear that not all people in the colony agreed with the sentiments of the miners. In New gold mountain some of the characters were among them. Who were these people? Were they real people in history or fictional characters? How do you know?

Ask students to use historical documents and information from the novel to write two short newspaper reports about the Lambing Flat riots – one for an Australian newspaper of the time and one for a Chinese language newspaper (not in Chinese) and annotate differences in point of view and emotive and descriptive language.

Students may recreate the riot described by Shu Cheong in an iMovie, animation or picture book. Have the character 'Jeremy' as the narrator.

Task 9: Friends of the Chinese

Jeremy and Shu Cheong

Ask students to read the diary entries in New gold mountain from Sunday, January 17 when Jeremy and Shu Cheong first meet, to Thursday, April 18 when they last see each other.

Organise the students into small groups to decide upon characteristics and circumstances that are shared by the two boys; their similarities. They write these in the centre column of the worksheet.

In their groups, students discuss key characteristics and circumstances of the boys that they do not share and write these in the columns under each boys' name.

| Shu Cheong

Different | Shu Cheong and Jeremy

Similar | Jeremy Different |

| Characteristics

| lonely

good at learning from watching

| friendly

keen to learn the customs of the other boy's culture

| very white skin

very round eyes

|

| Circumstances

| no family living with him

| living away from home

| lives with family

doesn't know about his ancestors

|

Students then discuss the boys' similarities and differences and use evidence from the text to support their opinions.

As a class discuss:

- How does the author build the characters of Shu Cheong and Jeremy?

- How do we know what Jeremy is thinking?

- How do we know what Shu Cheong is thinking?

Discuss point of view and writing a diary in the first person.

Ask students to imagine that Jeremy and Shu Cheong each have one opportunity to use Twitter. They each send a tweet describing their new friend. Each tweet can only contain a maximum of 140 characters. Students write the two tweets using conventional grammar, spelling and punctuation. Note that spaces and punctuation marks are counted as characters.

Every letter in an English word is one character but in Chinese, because of the pictorial script, one word may be one or two characters. Ask students to consider the amount of information that could be contained in a Chinese tweet compared to that in an English one. Twitter is used widely in advertising. What difference could it make when choosing a language to use in global advertising?

Create a tweeting wall on a large drawing of the Great Wall of China. On this wall students add tweets about what they find interesting about China and Australia's engagement with Asia. Remember to keep tweets to 140 characters or less. If students learn how to write some words as Chinese characters they may substitute these for the English words.

Task 10: The PEEL strategy

Which boy had the better life?

Students use the PEEL strategy to write a paragraph supporting their opinion. They explain and elaborate using evidence from the text and by making connections with their own background knowledge.

Model writing complex sentences and experiment with connecting subordinate clauses to the main clause to elaborate, extend and explain ideas.

| Opinion:

I think _____________ has the better life because …

|

P

State your point

|

|

E

Explain

|

|

E

Elaborate

|

|

L

Link back to your opinion

|

|

Task 11: Games

Adults and children's games are referred to in New gold mountain.

Ask students to list the games.

Jeremy taught Shu Cheong how to play jacks and marbles. Go to the eeny meeny website and find instructions for playing jacks (knucklebones).

Students read the instructions individually. Then, as a group, they help each other to understand the text.

Students teach themselves how to play a game by following the instructions for a game of their choice from Chinese Historical and Cultural Project: Traditional games.

Students create an instructional video or poster to teach someone a game that they know how to play. They should try to do so using as few words as possible.

Discuss the part games play in creating and maintaining friendships.

Ask students to imagine that Shu Cheong and Jeremy had the power to influence the miners. What strategies could they use to create friendships among the miners, crossing cultural barriers?

Task 12: Anti–Chinese sentiments

Students locate and identify a range of sources about anti-Chinese sentiments in Australia. They view posters, cartoons, newspaper articles and other documents and analyse them. Suggested sources appear below. Provide scaffolding for complex language and concepts as required.

For each source, students write notes on the following questions:

- Who wrote/created it?

- When did they write/create it?

- Why did they write/create it?

- What is its message?

- Is it reliable?

- Who was it written/created for?

- Whose 'voice' or point of view is represented?

- Who might agree with it?

- Who might disagree with it?

Students use their notes to help answer this fat question: What do these sources tell you about the attitudes and values of people in the Australian colonies in the 19th century?

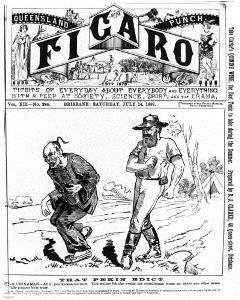

Source 1: Queensland Punch and Figaro, 1888

Image courtesy of the Collection of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Image courtesy of the Collection of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Source 2: The Mongolian octopus – his grip on Australia, 1886

Image courtesy of the Collection of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Image courtesy of the Collection of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Source 3: The yellow trash question, cartoon 1895

Image from e-Multicultural Research Library

Image from e-Multicultural Research Library

Source 4: Letter to the editor, excerpt, The West Australian, Thursday 16 June 1892

THE CHINESE IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA.

To THE EDITOR.

Sir – If we can be guided by the recent debate in the Legislative Assembly on the Chinese question, the political weather-cock indicates that sooner or later the Chinese will be either restricted or prohibited from coming to Western Australia. There can be little doubt, following the footsteps of the sister colonies as well as the United States, Western Australia will be anxious to rid herself of this alien race; the Chinese Immigration Act will be amended and the "Imported Labour Registry Act" repealed. We retain them (the Chinese) now … because they are indispensably useful. In the process of time, should it so happen, when we can grow our own vegetables, work our mines with European labour, find European cooks, and such like, it will be absolutely necessary that the useful Chinamen no longer useful to us, or at any rate less useful to us, should leave our Western shores and once more seek the land of his birth, when he again may be enabled to perform these periodical duties and ceremonies at the family shrine and the ancestral graves, the most sacred duties imposed upon the Chinese, which have been interrupted during his sojourn in a land which no longer tolerates him. It is not well for us to pause and analyse the reason why we do not tolerate him. As a rule Englishmen are generally fair, but sometimes we err so far as to become unfair.

…

We see the time coming – it may be very close – when the majority will be agreed that the Chinese shall no longer over-run our land. It is time that we considered the means of adopting whatever course we may decide upon to pursue. It seems to me that in dealing with this Chinese question and in legislating, for the restriction or prohibition of the Chinese, Australian statesmen are seldom if ever struck with the fact that in their discriminate treatment of the subjects of China they are violating international treaties. If we find the Chinese Government indignant at such a state of affairs it is not to be wondered at; they are indignant not because the Australian colonies frame laws of a domestic nature restricting the entry of an alien race, but because the subjects of China are singled out and discriminately treated … they object, and to my mind quite rightly, to the Australian colonies legislating against Chinese subjects and against Chinese subjects alone, and to impose a poll tax on Chinese immigrants and not on the immigrants of other foreign countries … Whatever may be our views in regard to this question … we must claim for the Chinese Government a certain amount of justice in their objection …

…

More is required of us as a great nation than that we should make restrictive measures of a discriminate character against a particular nation.

Yours, &c,

J.R. Carnarvon, June 6.

From the National Library of Australia

From: The West Australian (Public Domain)